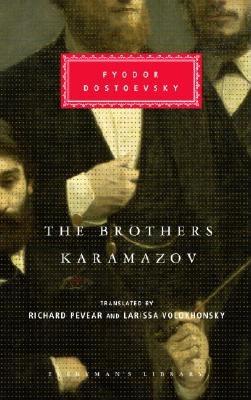

Last week I began a book that I have been wanting to read for a long time: namely, The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. I had to go through an adjustment period, but by the time I finished the first part of the novel, this period of adjustment was over. I am now done with the first part, and I wish to reflect upon the novel so far before I continue reading.

All that Dostoevsky talks about (through his characters), at first, seemed lofty and philosophical. Common conversations between characters include the following: the problem of suffering, faith and doubt, the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, the fall of man and human depravity, etc… In the beginning, this threw me off. However, I am now impressed with how Dostoevsky talks about these things. It is actually very plausible that his characters discuss these serious issues given the relationships his characters have in the novel. Alyosha (Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov), the main character, lives in a monastery. His father is a sensualistic money grubber. One brother is another sensualist, and the other is an atheist. This incites many deep conversations including the topics I mentioned. There are also trips and situations with elders and priests, as well as with prostitutes.

There are many specific situations, conversations, scenes, images, etc… that I could point out. I will mention only two, however.

First, I want to look at a mention of the term “happiness.” Zosima, an elder at the monastery, is the one who discusses happiness briefly. Zosima is a sort of mentor for Alyosha. Zosima is speaking to a woman whose daughter he has healed (the daughter’s health is still in question since her condition has merely improved). The mother’s name is Madam Khoklakhov, and the daughter’s name is Lise.

“For people are created for happiness, and he who is completely happy can at once be deemed worthy of saying to himself: ‘I have fulfilled God’s commandment on this earth.'” (p. 55)

So, what is happiness? Well, no specifics have been put forth explicitly by Zosima. He is an elder at a monastery, so it might be helpful to look at the creation of man in Genesis to try and understand Zosima’s worldview. I want to look at all of Genesis 1-2, but to be concise, I will quote only a few verses.

26 Then God said, “Let us make man[h] in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

27 So God created man in his own image,

in the image of God he created him;

male and female he created them.28 And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Gen. 1:26-28 ESV)

…

18 Then the Lord God said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for[e] him.” (Gen. 2: 18)

Man is created in the image of God (Imago Dei). God is triune, He is in relationship: the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Genesis 1 does not tell us that God needed his creation to be whole. Rather, it is out of this perfectly loving relationship of the trinity that creation happens. Love cannot help but create. And man was created in God’s image. Man was intended to live in relationship, he was intended to love. That is man’s purpose: to love. This is why I quoted Genesis 2:18 as well. To love – to do as God intended us – is to be happy. (The cultural mandate to be fruitful and multiply is one way that man can fulfill this call to be God’s image bearers on earth.)

In this quote, Zosima invokes the creation of man, but more specifically the purpose of man: why was man created? I would argue that Genesis, and the elder Zosima, say (even if implicitly) that man was created to love. Zosima says that man was created to be happy. Yes. I would argue that Zosima’s concept of happiness is directly rooted in the command to love in Genesis, and in the rest of Scripture. Happiness is the freedom and ability to love.

This actually leads to the second quote I wish to point out.

“Never be frightened at your own faintheartedness in attaining love, and meanwhile do not even be very frightened by your own bad acts. I am sorry that I cannot say anything more comforting, for active love is a harsh and fearful thing compared with love in dreams. Love in dreams thirsts for immediate action, quickly performed, and with everyone watching. Indeed, it will go as far as the giving even of one’s life, provided it does not take long but is soon over, as on stage, and everyone is looking on and praising. Whereas active love is labor and perseverance, and for some people, perhaps, a whole science. But I predict that even in that very moment when you see with horror that despite all your efforts, you not only have not come nearer your goal but seem to have gotten farther from it, at that very moment – I predict this to you – you will suddenly reach your goal and will clearly behold over you the wonder-working power of the Lord, who all the while has been loving you, and all the while has been mysteriously guiding you.” (p. 58, Zosima to Madame Khoklakhov)

The “goal” that Zosima discusses is to be happy, and, thus, to love. God’s commandment for us is happiness, and to be happy means to love. Happiness is the freedom and ability to love (I argue this based on Genesis 1 and 2 with the creation of man in God’s trinitarian image, and God’s commandment to be fruitful and multiply, a commandment to love and perpetuate love). And, in this second quote, Zosima defines the nature of this love – this active love.

The heavens opened this afternoon with rain and thunder. I love this kind of weather; it’s awesome, literally, awe-producing. Next to me is a cheerful yellow tea pot with masala chai, and it makes me feel loved because of the friend who gave it to me. I read your blog with interest. Zosima’s anthropology definitely has resonance with the Bible. Indeed, “people are created for happiness.” It seems many Christians are uneasy with the word “happiness” because of its pagan trappings with stoicism and epicureanism, but they need not be as long as it’s understood as “blessedness” (see: http://www.biblestudytools.com/dictionaries/bakers-evangelical-dictionary/blessedness.html).

What, then, is happiness – or blessedness? When Zosima says, “I have fulfilled God’s commandment on this earth,” I didn’t think of Genesis 1-2. Could he be referring to the commandment of double love (otherwise known as the “greatest commandment”) – to love God with one’s whole being and to love one’s neighbor as oneself? That seems more likely than the so-called “cultural mandate” (or “creation mandate”) in Gen. 1:28. If we say “happiness is the freedom and ability to love,” that’s true as far as it goes – but I don’t think it goes far enough. Blessedness is about man’s nearness to his Maker and eventual union with Christ at glorification. For evidence go no further than St. Paul in prison, who exudes happiness when he famously says, “For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain” (Phil. 1:21). Our happiness corresponds in degree with our closeness to God. So too, our misery corresponds in degree with our estrangement from God or, even worse, enmity toward God. All that said, we agree that our happiness is bound up with our capacity to love like God loves – inside and outside the Godhead. As a side note, what Bonaventure said in the 13th century dovetails nicely with what Dostoevsky said in the 19th century: https://bensonian.wordpress.com/2016/02/07/you-are-what-you-love/.

Finally, I appreciate your remarks about the “adjustment period” with The Brothers Karamazov. As readers, we need to be honest about the difficulties of reading – and how they differ from book to book and author to author. I can see how you were thrown off by lofty and philosophical conversations among the characters that may not bear much resemblance to how people really talk. Some critics of Dostoevsky think he emblematizes his characters; they only serve as symbolic representations of a quality or concept. At times, this criticism may be legitimate. Here, I think you’ve mounted a case for the plausibility of the conversations. I do want to ask these questions of application: Do you talk on a regular basis with people in your life about “the problem of suffering, faith and doubt, the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, the fall of man and human depravity”? If yes, what are the ingredients for having such a conservation? If not, what is missing? Are these kind of conversations even desirable to have on a regular basis? Or, should we be content with more ordinary exchanges between people? You and I love literature, but we should be aware that the escape of literature, which is one of its chief pleasures, can run the risk of escapism, where the elevated and dramatized life in literature leaves us dissatisfied with the modest life we actually experience.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply. First, I look at Genesis 1-2 because Zosima says “For people are CREATED for happiness.” I think that because of the language, that the creation account is a great place to look in response to this passage. Also, I did not mean to emphasize the cultural mandate too much. I actually intended to look at man’s being created in the image of God. I think that Genesis 1 gives us a sight into the purpose in God’s creation of man (I do want to be careful with not pushing Scripture for too many details). What I wanted to point to was God’s creation of man in God’s image, and what that entails: namely, that man was created to be in relationship in order to reflect the image of the triune God. To live in relationship and to love in relationship is to do as God intended, and that is what I think happiness looks like in Genesis 1 and throughout Scripture. I think that this is emphasized in the commandment of double love (to love God and neighbor). I mentioned the cultural mandate to look at a specific example of how man lives out his life in a way that reflects the image of the triune God. I do not think that man’s happiness lies in having sex and creating children, but rather in Christ, the example of love. I do think, however, that the command to be fruitful and multiply shows us a greater reality. The love of man and woman creating life is an image pointing the triune God’s love creating life in the beginning (in Genesis 1). I hope this explains a little bit more why I looked to the creation account. I will reread my post and make sure I said what I wished to say.

And with regards to the questions you ask. Would you like me to merely think about them, or answer them? If so, would you like me to respond to them here or via email or text?

LikeLike

To state the obvious, I have not read The Brothers Karamazov, so I may be missing important context. When I read this passage you quoted – “For people are created for happiness, and he who is completely happy can at once be deemed worthy of saying to himself: ‘I have fulfilled God’s commandment on this earth'” – I can see how it may point us to the creation account in Genesis, but I suspect that Zosima is referring to the greatest commandment when he speaks about fulfilling “God’s commandment on this earth.” God put on this planet to love Him and others.

And yes, please answer the questions I posed here in the comments, and try to be as specific and personal as possible. I’ll be interested in hearing your reply.

LikeLike

Well, what I would say is that God’s greatest commandment – to love God and to love others – is in Genesis 1. Yes, I think Zosima is referring to the commandment of double love. The commandment in the gospel account(s) is the same as the implicit commandment in creation. God created man in His image. God created out of love and God created man in order to love. I think this is why ‘to love God and neighbor’ is the greatest commandment. When you mention the double commandment in Mark 12, Matthew 22, and Luke 10, I do not see something separate from what is communicated in Genesis 1 by the creation of man Imago Dei. The commandment to love God and love neighbor is what God intended man to do by creating him in His image.

I have talked with people throughout this year about all of those things in some way. This is often with fellow Christians whether its in some sort of small group setting, or whether its just two or three of us just talking. But, there are also people in my fraternity who have asked my serious questions, and our chapter Bible Study opened up a setting in which those types of topics can be discussed. What is needed for these sorts of talks is probably honesty. People need to feel free to express their thoughts and emotions. Also, something that would encourage these deeper conversations is humility; we don’t know everything. I don’t know everything. That’s extremely helpful when talking about things like the problem of suffering.Yes, I do think that these types of conversations are desirable. Are they the only types of conversations I want to have? By all means, no.

LikeLike

Joey, your clarification is helpful. We are on the same page by interpreting what Zosima is referring to when he speaks about fulfilling “God’s commandment on this earth.” I entirely agree that the commandment of double love is rooted in our creational design but it nonetheless was needed to be made explicit because, after the Fall, man’s design was distorted, resulting, above all else, in love of self rather than love of God and neighbor. Put differently, we should link anthropology (who we are) with ethics (what we should do).

Switching to the other topic, I often have serious theological and philosophical conversations with people, whether it be with my students, colleagues, or friends. But I have learned that an exclusive diet of such conversations is not salutary precisely because, as human beings, we are not made for ideas alone. That is why some of Dostoevsky’s critics are right to at least raise the question about whether he emblematizes his characters in such a way that they lack resemblance to flesh-and-blood human beings, who talk about ice cream, auto maintenance, and grading papers more often than the problem of suffering and the immortality of the soul.

LikeLike

I agree with what you have said. Despite the emphasis on these lofty conversations, there are mundane ones in the novel as well. Dostoevsky does tend to include more philosophy in everyday discussions than other authors. This may not be characteristic of my life experience with conversations. But this could have been the way in Dostoevsky’s life. The conversations in the novel, how many are philosophical, how many more common, could be normative for Dostoevsky’s actual experience. I need to read more of Frank’s biography to investigate this.

LikeLike

Dostoevsky’s fiction raises this question for me: Should storytelling be in service of philosophy or should philosophy be in service of storytelling? I’m not acquainted with a novelist that’s more philosophical than Dostoevsky, although Wilder possesses some of that Russian gravitas. Dostoevsky wears philosophy on his sleeve, whereas Dickens and Austen are coy and indirect.

LikeLike